As we often discuss, in recent decades election observation has become crucial to improving democracy and promoting human rights across the globe. Not only does it help improve electoral systems by review, it also dissuades electoral fraud, promotes public confidence in the electoral process, and produces more valid elections. Since the first monitored plebiscite took place in modern day Romania in 1857, the practice has grown as a way of legitimising and improving elections, especially since World War II and increasingly since the end of the Cold War. One of the aspects of domestic and international observation which can often be confusing, even after understanding more about observation, is knowing which groups carry out the practice. Perhaps it’s just the endless abbreviations or maybe the cross-over between these groups work, but I thought it may be a good idea to highlight the main organisations operating in the field.

European Union/ EU EOMs

Every year the European Union spends thirty-eight million Euros conducting around ten observation missions to third countries in regions such as Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. This is done to reflect the EU’s ‘commitment to supporting democracy and promoting human rights around the world’ with a focus on fragile and developing states. These observations include a mixture of Long-Term and Short-Term Observers and helps increase public confidence and promote participation in elections whilst reducing the chances of election related conflicts occurring. This is reflected in the following report produced, which provides not only suggestions on how to improve the integrity of future elections but also the wider process of democratisation. The EU does not observe elections within EU states – those are conducted by…

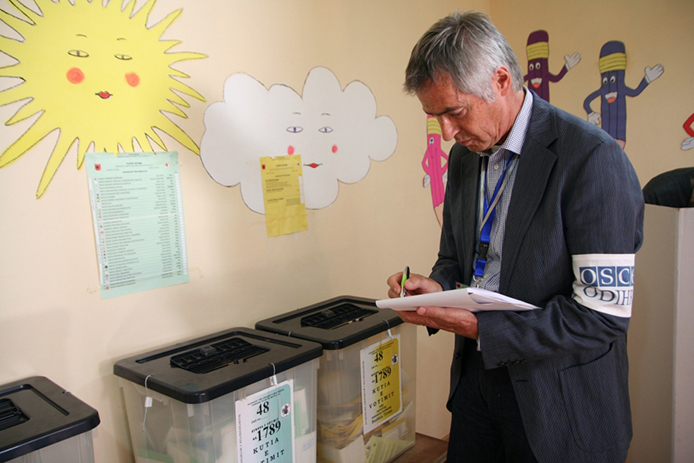

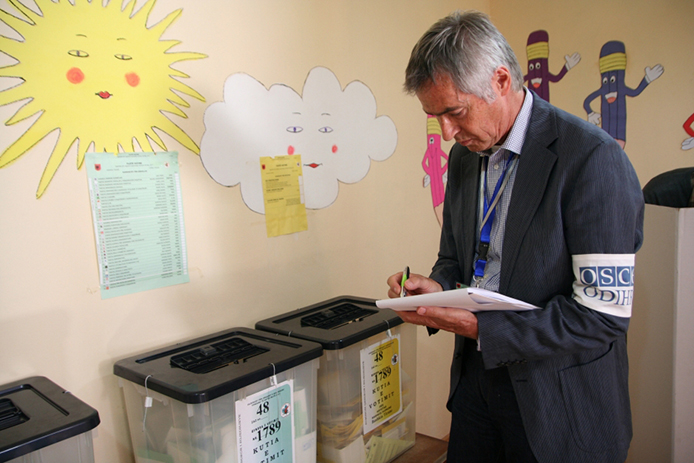

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe/ ODIHR

The OSCE is an inter-governmental organisation, with member states present across Europe, central Asia and North America with a focus on improving security through human rights, arms control and freedom of the press. In addition to this, the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), a branch of the OSCE, is responsible for promoting democratic elections in the member states judging their elections for their ‘equality, universality, political pluralism, confidence, transparency and accountability’. In recent years observations have moved away from emerging democracies towards more established ones in an attempt to scrutinise the role of technology in elections and the rise of early and postal voting. Unlike the EU it only observes elections within the member states of the OSCE.

Council of Europe

Often confused with the European Union, in my case due to the then European Communities adoption of the council’s flag in 1985, the Council of Europe is advised by the Venice Commission (comprised of independent experts in constitutional law) and aims to protect voters rights and enhance the capacity of national electoral stakeholders. In addition to training domestic observers, the Division of Electoral Assistance helps national election administration, encouraging voter participation and shift electoral legislation.

UNEAD

The United Nations Electoral Assistance Division has recently scaled back the number of election observation missions it undertakes following the practice’s widespread use in the 1990s. At this time following decolonisation and the shifting of electoral responsibility to newly democratised countries, the organisation oversaw landmark elections in nations such as Timor-Leste, Cambodia and El Salvador. In some transitional cases, such as the former, the UN has been fully responsible for the organisation and conduct of the whole election in order to provide the result validity and encourage a peaceful election. In more recent times assistance has been provided to through technical and logistical assistance in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Iraq, although gaining this assistance requires a mandate from the General Assembly or the Security Council limiting their number, often under the banner of peacekeeping or as special political missions. In total over 100 member states have been assisted across over 300 elections and plebiscites, though much of their work has overseen broader issues than other organisation’s observation missions.

Domestic Groups

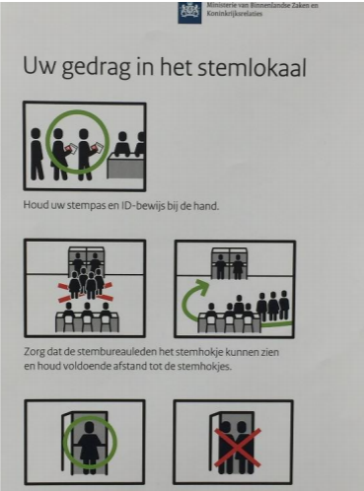

The final group to discuss is that of domestic electoral groups.

These groups are generally part of the Global Network of Domestic Election Monitors (GNDEM) which currently comprises of 251 organisations in 89 countries and territories. These groups differ significantly from the others mentioned as they are a direct way for citizens to be involved easily in electoral observations and scrutinise the democratic process which protects the rights of people ‘to participate in electoral and political processes’. Non-partisan observers will often visit a larger amount of polling stations compared to intergovernmental organisations, providing a wider understanding of election day activities through data collected from activities occurring in polling stations such as disabled access, family voting and of political actors in the polling stations vicinity.

Of course, this list is not exhaustive and other groups do exist across the world, for example regional organisations such as the Arab Network for Democratic Elections and the East and Horn of Africa Election Observers Network operate as members of GNDEM, carrying out vital work in these regions.

There are then, many observation organisations operating across the globe, from smaller citizen led observation groups to those run by the biggest intergovernmental organisations. Their rapid spread since the 1990s has demonstrated an increased will from nations, international organisations and citizens to promote the spread of democracy across the world and enhance it at home.

Harry Busz is editor of The Election Observer

You must be logged in to post a comment.