Family voting, also referred to as group voting, is one of the most common issues that observers encounter in polling stations. For example, during two recent Democracy Volunteers observations in Northern Ireland and The Netherlands the violation was witnessed in 44% and 11% of polling stations monitored respectively (Democracy Volunteers, 2019a & b). But what is family voting and why does it matter?

What Is it?

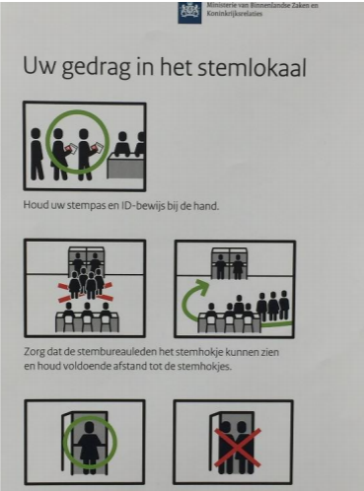

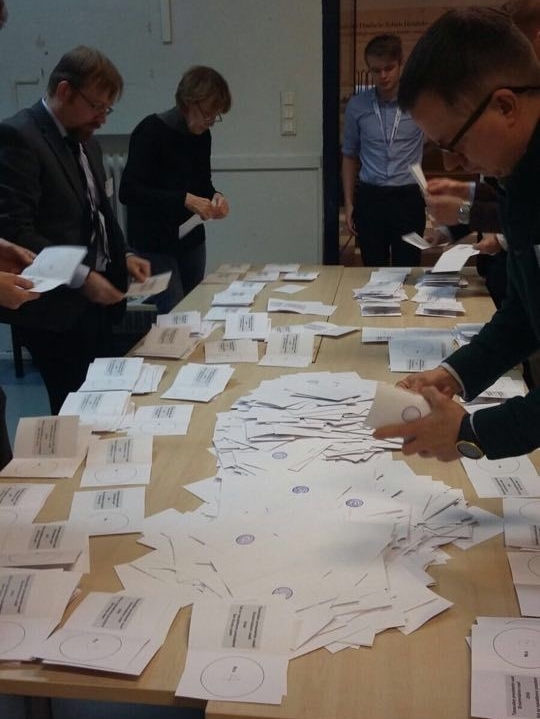

Family voting is defined by the OSCE as ‘Where more than one voter is present in a polling booth or behind a voting screen at the same time. The term “family voting” is sometimes used even though it is not always the case that a group of voters are members of one family’ (OSCE/ODIHR,2010). It can take a variety of forms such as two voters entering a single polling booth to cast their ballot, to talking in a queue whilst waiting to vote. During observations it is not extremely rare to witness a (literal) whole family of four or five voters deciding on a candidate at the polling booth together or for a parent to physically mark a ballot belonging to their adult children or partner. Many participants do not know what they are doing is against electoral law and polling staff are often too busy, distracted or intimidated to intervene. In order to dissuade the practice voters are often presented with a poster as can be seen in the photo below although these are not a necessity in many elections.

Why is it important?

The main issue surrounding family voting is that it prevents the right for a voter to cast a secret ballot in line with paragraph 5.1 of the Copenhagen Document’s commitments (CSCE, 1990). This is a fundamental right for voters as it protects their political privacy reducing the chances of intimidation and blackmail, ensuring their free expression of opinion increasing the validity of the vote.

The practice is seen to disproportionately effect certain groups of voters, such as first-time voters, non-native speakers and women. As described by a National Democratic Institute and iKNOW report (2009), women’s voting rights are especially at risk in communities where social and cultural voting norms are dictated by a history of male family heads deciding which political candidate will gain a group/family’s support. First-time voters are also often witnessed family voting as they are unsure about the voting system and often seek assistance from those accompanying them, as may be voters who experience a language barrier. For this reason, it is especially important that these voters are helped to understand the process of voting by election officials, outside of the polling booth, with no chance for coercion.

CSCE (1990) Document of the Copenhagen meeting of the conference on the human dimension of the CSCE. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/14304?download=true

Democracy Volunteers (2019a) The Netherlands Final Report. https://democracyvolunteers.org/2019/05/16/final-report-netherlands-provincial-and-water-board-elections-20-03-19/amp/?__twitter_impression=true

Democracy Volunteers (2019b) Preliminary Statement- Northern Ireland local elections 02/05/2019. https://democracyvolunteers.org/2019/05/04/preliminary-statement-northern-ireland-local-elections-02-05-19/

NDI & iKNOW (2009) Consolidated response on the prevention of family voting. https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/Consolidated%20Response_Prevention%20of%20Family%20Voting.pdf

OSCE/ODIHR (2010) Election Observation Handbook 6th edn. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/68439?download=true

Harry Busz is editor of The Election Observer

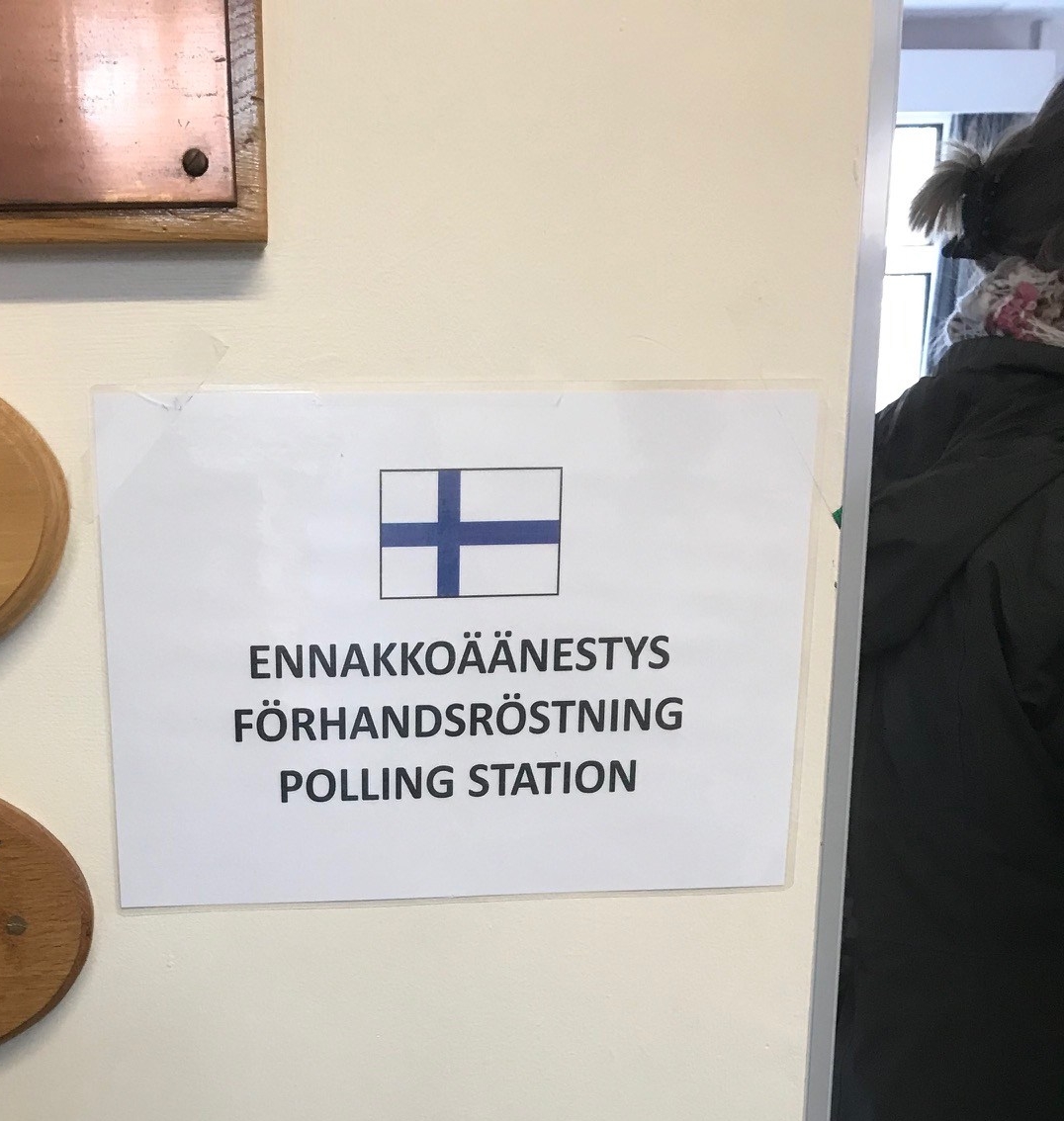

Between the 3rd and 6th of April, polling stations were open across the UK for voters to cast their ballot in the Finnish Parliamentary Elections. From the Embassy in London all the way to Aberdeen, 2494 voters participated in the process, up from 2060 back in 2015. Democracy Volunteers sent teams across the country to observe the process and are currently arriving across Finland to observe the domestic vote on Sunday the 14th.

Between the 3rd and 6th of April, polling stations were open across the UK for voters to cast their ballot in the Finnish Parliamentary Elections. From the Embassy in London all the way to Aberdeen, 2494 voters participated in the process, up from 2060 back in 2015. Democracy Volunteers sent teams across the country to observe the process and are currently arriving across Finland to observe the domestic vote on Sunday the 14th. The voting process itself took place in a small room just off the hall, where two polling staff had created their own ballot box and voting booth out of a cardboard box adorned with the Finnish flag and draped in the national colours of Blue and White. After talking to staff and voters in the hall it became clear that the democratic process was one that was celebrated greatly and gave a sense of immense national pride. It is this culture, we were told, that formed the basis of the trust in the system, with unsecured ballot boxes not seen as an issue due to the trusting nature of the community.

The voting process itself took place in a small room just off the hall, where two polling staff had created their own ballot box and voting booth out of a cardboard box adorned with the Finnish flag and draped in the national colours of Blue and White. After talking to staff and voters in the hall it became clear that the democratic process was one that was celebrated greatly and gave a sense of immense national pride. It is this culture, we were told, that formed the basis of the trust in the system, with unsecured ballot boxes not seen as an issue due to the trusting nature of the community. One of the key aspects of effective election observation is that observers may arrive at polling stations unannounced, at any time, during the voting or counting process. The reason for this may seem obvious, but if any observer were to have to inform a polling station of a visit, the actions of polling staff might change and not be a proper representation of their normal conduct.

One of the key aspects of effective election observation is that observers may arrive at polling stations unannounced, at any time, during the voting or counting process. The reason for this may seem obvious, but if any observer were to have to inform a polling station of a visit, the actions of polling staff might change and not be a proper representation of their normal conduct. Our three teams were challenged a total of five times throughout the day, sometimes held at length, impeding the work they intended to carry out. Not only is this a contravention of the guidance of the Electoral Commission, but it more importantly, prevents observers from being able to give valuable feedback to officials running elections and ensuring democracy is practiced properly. For this reason, it is crucial that up-to-date guidelines are maintained, and these are distributed properly by councils to their polling station staff, so that issues such as this don’t arise in the future.

Our three teams were challenged a total of five times throughout the day, sometimes held at length, impeding the work they intended to carry out. Not only is this a contravention of the guidance of the Electoral Commission, but it more importantly, prevents observers from being able to give valuable feedback to officials running elections and ensuring democracy is practiced properly. For this reason, it is crucial that up-to-date guidelines are maintained, and these are distributed properly by councils to their polling station staff, so that issues such as this don’t arise in the future.

I am regularly asked, when I am observing an election in a western country, like the UK: ‘shouldn’t you be somewhere where democracy is not as established?’ or something equivalent. I then explain that ‘no democracy is perfect’ and justify why we, at Democracy Volunteers, have deployed dozens of observers across areas like Surrey where there is no belief that election observation is necessary.

I am regularly asked, when I am observing an election in a western country, like the UK: ‘shouldn’t you be somewhere where democracy is not as established?’ or something equivalent. I then explain that ‘no democracy is perfect’ and justify why we, at Democracy Volunteers, have deployed dozens of observers across areas like Surrey where there is no belief that election observation is necessary.

You must be logged in to post a comment.